Explaining the Chiropractic Adjustment

Comparing and Contrasting the Audible (“Pop, Crack”) to the Non-Audible Adjustment And Clinical Outcomes

Chiropractic care does not involve drugs or surgery. Chiropractic care centers around the application of mechanical forces to a patient’s body, and primarily to their spine.

Untrained lay practitioners who apply mechanical forces to a patient’s body call such a maneuver a manipulation. Manipulation implies that the delivered force is rather nonspecific in terms of direction (line-of-drive), depth (amplitude), and speed (velocity).

In contrast, when chiropractors apply mechanical forces to a patient, they call such a maneuver an adjustment. Adjustments are delivered by chiropractors who are trained to control the line-of-drive, depth, and speed. The benefits of these adjustments are well documented, especially for low back pain and neck pain syndromes (1, 2).

As an example, in 1990, a study was published in the British Medical Journal, titled (2):

Low Back Pain of Mechanical Origin:

Randomized Comparison of Chiropractic and Hospital Outpatient Treatment

This randomized controlled trial involved 741 patients aged 18-65. These patients were followed up for two or even three years. The main outcome measures included the score on the Oswestry pain disability questionnaire, straight leg raising, and lumbar flexion. Each patient was re-evaluated at weekly intervals for six weeks, at six months, and at one and two years after entry into the study.

The authors found that chiropractic treatment was more effective than hospital outpatient management, mainly for patients with chronic or severe back pain. Fewer patients treated in the hospital were satisfied with their treatment or relieved with their symptoms than by those treated by chiropractors. The authors stated:

“There is, therefore, economic support for use of chiropractic in low back pain, though the obvious clinical improvement in pain and disability attributable to chiropractic treatment is in itself an adequate reason for considering the use of chiropractic.”

“The results leave little doubt that chiropractic is more effective than conventional hospital outpatient treatment.”

“The confidence intervals for the differences in Oswestry scores were wide, but the degree of improvement recorded for many of the secondary outcome measures suggests that chiropractic has appreciable benefit.”

“The effects of chiropractic seem to be long term, as there was no consistent evidence of a return to pretreatment Oswestry scores during the two years of follow up, whereas those treated in hospital may have begun to deteriorate after six months or a year.”

“Chiropractic was particularly effective in those with fairly intractable pain-that is, those with a history of severe pain.”

“The results from the secondary outcome measures suggest that the advantage of chiropractic starts soon after treatment begins.”

“… this pragmatic comparison of two types of treatment used in day to day practice shows that patients treated by chiropractors were not only no worse off than those treated in hospital but almost certainly fared considerably better and that they maintained their improvement for at least two years.”

Important to this discussion is the understanding that the hospital-managed patients were very often manipulated by hospital personnel that have less training than chiropractors. The following month, the journal The Lancet published an editorial which included the following (3):

“[The article] showed a strong and clear advantage for patients with chiropractic.”

“This highly significant difference occurred not only at 6 weeks, but also for 1, 2, and even (in 113 patients followed so far) 3 years after treatment.”

“Surprisingly, the difference was seen most strongly in patients with chronic symptoms.”

“The trial was not simply a trial of manipulation but of management” as 84% of the hospital-managed patients had [non-chiropractic] manipulations.

“Chiropractic treatment should be taken seriously by conventional medicine, which means both doctors and physiotherapists.”

“Physiotherapists need to shake off years of prejudice and take on board the skills that the chiropractors have developed so successfully.”

The understanding of the chiropractic approach to using mechanically-based care was significantly enhanced with the Nobel Prize work that was awarded in 2021 (4, 5).

•••••

Within the community of chiropractors there are many accepted and beneficial approaches. The different approaches are called techniques. The accepted techniques within the chiropractic profession number into the dozens and perhaps as many as one hundred. Some chiropractors practice only one technique. Others practice an amalgamation of a number of techniques.

Examples of some commonly practiced techniques include: Gonstead, Sweat, Thompson, Active Release, Nimmo, NUCCA, Toggle, Drop Table, Activator, Blocking, Flexion Distraction, Diversified

Some of these techniques use High Velocity-Low Amplitude (HVLA) thrust applications. HVLA techniques are classically associated with an audible, palpable sensation, often described as a “pop” or “crack” by patients and chiropractors alike.

Other techniques are not associated with an audible, palpable “pop” or “crack.”

Patients who have been to more than one chiropractor often develop a preference for one technique or another, and they often will actively seek the care from a chiropractor that practices their preferred technique. Both approaches, the audible and the non-audible techniques have both their advocates and cynics among chiropractors and among chiropractic patients.

Velocity

As described above, chiropractic adjustments are often referred to as High Velocity-Low Amplitude (HVLA) maneuvers.

Technically, velocity is the change in position over a period of time. For this discussion, velocity will be used synonymously with speed. An understandable analogy is the moving of a motor vehicle. A vehicle might be traveling at 60 miles per hour, meaning the distance will change 60 miles in 60 minutes, or 1 mile per minute.

Vehicles move lineally along the road. In contrast, the joints of the human body move angularly, along arcs of circles. Movements in arcs of circles are measured in degrees.

Velocity is non-injurious, including high velocity:

- While driving in a vehicle at 60 miles per hour, one is not injured.

- While flying in an airplane at 500 miles per hour, one is not injured.

- While standing on planet earth, which is spinning at about 1,000 miles per hour, one is not injured (it takes 24 hours for the new day to begin, meaning the earth has rotated about 25,000 miles in 24 hours).

The fastest human motion is finger snapping, which makes an audible noise but is non-injurious (6). Its rotational velocity “is an astounding 7,800 degrees per second — three times as fast as a pro baseball player’s arm” (6).

Acceleration

Acceleration is a change in velocity over a period of time. For this discussion, it would be an increasing or decreasing of speed (velocity).

Acceleration can be injurious, depending on its rate:

- While driving in a vehicle at 60 miles per hour, one is not injured (velocity). However, if one was traveling at 40 miles per hour and then rear-ended by a truck traveling much faster and accelerating your vehicle to 60 miles per hour within a second, you would sustain a whiplash injury (from the rapid acceleration, increasing velocity from 40 to 60 miles per hour within 1 second).

- While flying in an airplane at 500 miles per hour, one is not injured (velocity). When the pilot prepares for landing, he/she will slowly decelerate (decrease speed) over a period of minutes to zero when parked at the gate. Again, there are no injuries. However (this analogy is very crude but sadly understandable, apologies), if the plane traveling at 500 miles per hour reduced its speed to zero by running into a hill, there would be no survivors.

- While standing on planet earth, which is spinning at about 1,000 miles per hour, one is not injured (velocity). However, if earth instantly stopped spinning, we would all be thrown into space.

Amplitude

Amplitude, for this discussion, refers to the distance the joint moves. When chiropractors adjust joints, they are trained not to exceed the limit (amplitude) of anatomic motion. This is referred to as using low-amplitude. If the amplitude is excessive, it could cause an injury.

•••••

When a force is applied to a joint, increased motion and “joint separation” occur. This can be done without causing any injury to the joint tissues (bones, cartilage, ligaments, muscles, tendons, nerves, etc.). This increased motion has a number of proposed benefits, including (7):

- The disruption of intra-articular and peri-articular adhesions.

- The remodeling of peri-articular fibrosis.

- Generating spinal cord reflexes that inhibit muscle tone and spasm.

- Improving proprioception to inhibit pain by closing the pain gate.

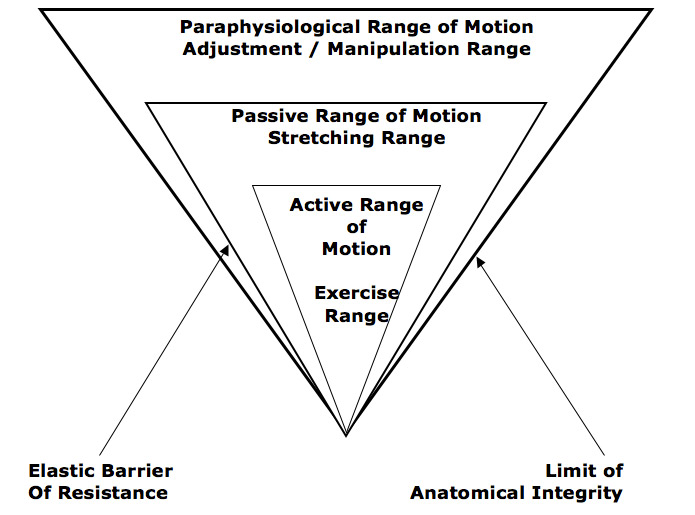

The audible joint cavitation process was initially described in 1976 where joint motion was described in three categories (8). This model of joint cavitation is supported by others (7, 9) and is explained as follows:

Active Range of Motion (7): This is the motion that occurs as a consequence of performing exercise.

Passive Range of Motion (7): This is the motion that occurs as a consequence of stretching and/or through mobilization techniques.

“Beyond the end of the active range of motion of any synovial joint, there is a small buffer zone of passive mobility.” A joint can only move into this zone with passive assistance, and going into this passive range of motion “constitutes mobilization.” [not manipulation.]

Peri-articular Paraphysiological Space Motion (7):

“At the end of the passive range of motion, an elastic barrier of resistance is encountered.”

“If the separation of the articular surfaces is forced beyond this elastic barrier, the joint surfaces suddenly move apart with a cracking noise.”

“This additional separation can only be achieved after cracking the joint and has been labeled the paraphysiological range of motion. This constitutes manipulation.”

“The cracking sound on entering the paraphysiological range of motion is the result of sudden liberation of synovial gases—a phenomenon known to physicists as cavitation.”

“At the end of the paraphysiological range of motion, the limit of anatomical integrity is encountered. Movement beyond this limit results in damage to the capsular ligaments.”

Joint adjusting “requires precise positioning of the joint at the end of the passive range of motion and the proper degree of force to overcome joint coaptation” (to overcome the resistance of the joint surfaces in contact).

Joint Ranges of Motion

Over many decades, bioengineers and physicians have investigated joint cavitation with associated audibles as a biophysical phenomenon and for safety (10, 11, 12, 13, 14).

•••••

Important for the understanding of the value of joint adjusting are the discussions presented by William H, Kirkaldy, MD, and his colleague J. David Cassidy, DC (7, 16). Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis was (d. 2006) a Professor Emeritus of Orthopedics and director of the Low-Back Pain Clinic at the University Hospital, Saskatoon, Canada. Drs. Kirkaldy-Willis and Cassidy emphasized that in cases of chronic low back pain, there is a shortening of periarticular connective tissues and intra-articular adhesions may form; spinal adjustments can stretch or break these adhesions. This would improve ranges of motion, improve biomechanical function, reduce articular stress and consequent inflammation, and therefore reduce pain. This is the standard and plausible orthopedic explanation for the benefits of the chiropractic adjustment.

Another plausible explanation for the benefits of the chiropractic adjustment profiles neurological reflexes and the 1965 Gate Theory of Pain, originally proposed by Patrick Wall and Ronald Melzack (17). This theory has “withstood rigorous scientific scrutiny (18).”

The Gate Theory proposes that the central transmission of pain can be blocked by increased proprioceptive input because pain is facilitated by the “lack of proprioceptive input.”

The facet capsules are densely populated with mechanoreceptors. “Increased proprioceptive input in the form of spinal mobility tends to decrease the central transmission of pain from adjacent spinal structures by closing the gate. Any therapy which induces motion into articular structures will help inhibit pain transmission by this means.” [Important]

Stretching of facet joint capsules will fire capsular mechanoreceptors which will reflexively “inhibit facilitated motoneuron pools” which are responsible for the muscle spasms that commonly accompany low back pain.

•••••

Critical to understanding the benefits of the chiropractic adjustment as related to the audible release versus the chiropractic adjustment without the audible release appeared in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, in an article titled (15):

The Audible Release Associated with Joint Manipulation

The paper was authored by Raymond Brodeur, a chiropractor and engineer working at Michigan State University.

Dr. Brodeur emphasizes that the key to the benefits of joint adjusting is linked to the velocity (speed). His basic premise is that the cavitation associated with the audible adjusting of a spinal segment has sufficient speed to fire off high-threshold mechanoreceptors, inhibiting segmental muscle tone, and improving motion. This would close the Pain Gate of Drs. Melzack and Wall.

Dr. Brodeur asserts that during the “crack” associated with a joint manipulation, there is a sudden joint distraction that occurs in less time (meaning with sufficient speed) than that required to complete the stretch reflexes of periarticular muscles. He proposes that the cavitation process is generated by an elastic recoil of the synovial capsule as it “snaps back” from the capsule/synovial fluid interface.

Because the sudden joint distraction during the adjustment occurs in a shorter time period than that required to complete the stretch reflexes of the periarticular muscles, there is likely to be a high impulse acting on the ligaments and muscles associated with the joint. This explanation proposes that reflex actions from high threshold periarticular receptors are associated with the many beneficial results of manipulation.

This suggests that the cavitation process provides a simple means for initiating the reflex actions and that without the cavitation process, it would be difficult to generate the forces in the appropriate tissue without causing muscular damage.

Most relevant to this discussion, Dr. Brodeur also makes the point that chiropractic drop tables and Activator adjusting instruments are capable of achieving the same mechanical benefits because the speed required to initiate the beneficial reflexes are built into these mechanical devices.

In other words, the key is speed. The speed initiates the beneficial reflexes. The speed can be achieved by either:

- Joint cavitation with the associated audible “pop” or “crack.”

- Mechanical instruments that do not necessarily cause joint cavitation, but can deliver sufficient speed to initiate the beneficial reflexes.

•••••

In 2002, the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association published a study titled (19):

Joint Cracking and Popping:

Understanding Noises that Accompany Articular Release

The authors, from Good Samaritan Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA, note that the physiological benefits of joint adjusting can occur with or without the audible “pop.” This point was further examined, in detail, in 2022 when the journal Chiropractic & Manual Therapies published a study titled (20):

Impact of Audible Pops Associated with Spinal Manipulation on Perceived Pain:

A Systematic Review

The objective of this study was to update the evidence to determine if the “pop” from a manipulation had any therapeutic benefit. The authors searched these electronic databases: PubMed, Index to Chiropractic Literature, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature and Web-of-Science. The authors identified five original research articles that met their inclusion criteria and were included in this review: 4 were prospective cohort studies and 1 was a randomized controlled trial. A total of 303 participants between the ages of 18 and 65, of which 39% were male and 61% were female.

The authors note that historical theories claim that spinal adjusting is used to restore joint function and mobility, which decreases pain and improves function. They also note the plausibility and benefit of initiating spinal neurological reflexes.

Consistent with mechanisms stated above, these authors describe the adjustment as:

“Typically, with high-velocity low-amplitude (HVLA) [adjustment] the target joint is brought to its end range of motion as the practitioner applies a directed preload force followed by a thrust.”

“The force delivered takes the joint beyond its regular end range of motion, allowing the joint to move into the para-physiological movement zone.”

The authors also state:

“An audible pop is the sound that can derive from an adjustment in spinal manipulative therapy and is often seen as an indicator of a successful treatment.”

“Chiropractic patients are familiar with hearing a popping or cracking sound when receiving [an adjustment] and this is often seen as a factor that differentiates mobilization and manipulation.”

“To the clinician delivering [spinal adjustments], this sound is frequently associated with the perception of a successful intervention and when it does not occur, some clinicians may apply another treatment thrust.”

The papers reviewed concluded that neither an audible “pop” or lack of an audible “pop” had any impact on improvements of pain or function. Specifically, the authors stated:

“All studies reported similar results: regardless of the area of the spine manipulated or follow-up time, there was no evidence of improved pain outcomes associated with an audible pop.”

“Audible pops generated during the application of [an adjustment] are not likely to possess independent therapeutic benefit in their impact on pain outcomes.”

“The presence or absence of an audible pop may not be important regarding pain outcomes with spinal manipulation.”

“There is currently an absence of evidence that supports a relationship between the presence of an audible pop during the delivery of [an adjustment] and pain outcomes.”

“It is possible that the audible pop sound has a psychological effect, not only affecting the patient but also affecting the chiropractor and when patient’s expectations of hearing an audible pop during [an adjustment] are not fulfilled it may have a negative effect on the clinical outcome.”

“In terms of clinical practice then, this review supports the notion that clinicians need not overemphasize the presence of a perceived AP as an indicator of successful treatment.”

SUMMARY

The information presented here indicates that speed is the key because speed activates beneficial reflexes that are not obtainable without speed. The joint cavitation process with an associated audible pop has the necessary beneficial physiological speed built into it.

Additionally, the benefits of speed can be obtained without cavitation and an audible pop. This is most likely to occur with the use of hand-held mechanical adjusting devices and drop-table mechanisms.

The bottom line is that both the chiropractor and the patient should find the approach that they are most comfortable with.

REFERENCES:

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank AO; Low Back Pain of Mechanical Origin: Randomized Comparison of Chiropractic and Hospital Outpatient Treatment; British Medical Journal; June 2, 1990; Vol. 300; pp. 1431-1437.

- editorial; Chiropractors and Low Back Pain; The Lancet; July 28, 1990; Vol. 336; p. 220.

- Roland D, Abott B; Nobel Prize in Medicine Awarded for Work on Senses; Wall Street Journal; October 5, 2021.

- Zylka MJ; A Nobel Prize for Sensational Research; New England Journal of Medicine; December 16, 2021; Vol. 385; No. 25; pp. 2393-2394.

- Acharya R, Challita EJ, Ilton M, Bhamla MS; The ultrafast snap of a finger is mediated by skin friction; Journal of the Royal Society Interface; November 17, 2021; 18; No. 184; Article 20210672.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Sandoz R; Some physical mechanisms and effects of spinal adjustment; Ann Swiss Chiropractic Association; 1976; Vol. 6; pp. 91–141.

- Fischgrund JS; Neck Pain; monograph 27; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2004.

- Roston JB, Wheeler-Haines R; Cracking in the Metacarpo-Phalangeal Joint; Journal Of Anatomy; Vol. 81; Part 2; 1947; pp. 165-173.

- Unsworth A, Dowson D, Wright V; ‘Cracking joints’ A bioengineering study of cavitation in the metacarpophalangeal joint; Annals of Rheumatic Diseases; 1971; Vol. 30; pp. 348–358.

- Gregory N. Kawchuk GN, Jerome Fryer J, Jacob L. Jaremko JL, Hongbo Zeng H, Lindsay Rowe L, Richard Thompson R; Real-Time Visualization of Joint Cavitation; Public Library of Science One (PLOS ONE); April 15, 2015; Vol. 10; No. 4; pp. e0119470.

- Swezey RL, Swezey SE; The Consequences of Habitual Knuckle Cracking; Western Journal of Medicine; May 1975; Vol. 122; pp. 377-379.

- deWeber K, Olszewski M, Ortolano R; Knuckle Cracking and Hand Osteoarthritis; American Board of Family Medicine; March-April 2011; Vol. 24; No. 2; pp. 169-174.

- Brodeur R; The audible release associated with joint manipulation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; March-April 1995; Vol. 18; No. 3; pp. 155-164.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Managing Low Back Pain; Churchill Livingston; (1983 & 1988).

- Melzack R, Wall P; Pain Mechanisms: A New Theory; Science; November 19, 1965; Vol. 150; No. 3699; pp. 971-979.

- Dickenson AH; Gate Control Theory of Pain Stands the Test of Time; British Journal of Anaesthesia; June 2002; Vol. 88; No. 6; pp. 755-757.

- Protapapas MG, Cymet TC; Joint cracking and popping: Understanding noises that accompany articular release; Journal of the American Osteopathic Association; May 2002; Vol. 102; No.5; pp. 283-287.

- Moorman AC, Newell D; Impact of Audible Pops Associated with Spinal Manipulation on Perceived Pain: A Systematic Review; Chiropractic & Manual Therapies; October 4, 2022; Vol. 30; No. 1; Article 42.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”